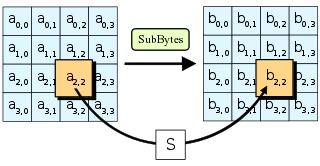

The SubBytes step, one of four stages in a

round of AES |

| General |

| Designers |

Vincent Rijmen,

Joan Daemen |

| First published |

1998 |

| Derived from |

Square |

| Successors |

Anubis,

Grand Cru |

| Certification |

AES winner,

CRYPTREC,

NESSIE,

NSA |

| Cipher detail |

|

Key sizes |

128, 192 or 256 bits[1] |

|

Block sizes |

128 bits[2] |

| Structure |

Substitution-permutation network |

| Rounds |

10, 12 or 14 (depending on key size) |

| Best public

cryptanalysis |

|

All known attacks are computationally infeasible. For AES-128,

the key can be recovered with a computational complexity of 2126.1

using

bicliques. For biclique attacks on AES-192 and AES-256, the

computational complexities of 2189.7 and 2254.4

respectively apply.

Related-key attacks can break AES-192 and AES-256 with

complexities 2176 and 299.5, respectively. |

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is a

specification for the

encryption of electronic data established by the U.S.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2001.[3]

Originally called Rijndael, the

cipher

was developed by two

Belgian

cryptographers,

Joan Daemen and

Vincent Rijmen, who submitted to the AES selection process.[4]

AES has been adopted by the

U.S. government and is now used worldwide. It supersedes the

Data Encryption Standard (DES),[5]

which was published in 1977. The algorithm described by AES is a

symmetric-key algorithm, meaning the same key is used for both

encrypting and decrypting the data.

In the

United States, AES was announced by the NIST as U.S.

FIPS PUB 197 (FIPS 197) on November 26, 2001.[3]

This announcement followed a five-year standardization process in which

fifteen competing designs were presented and evaluated, before the

Rijndael cipher was selected as the most suitable (see

Advanced Encryption Standard process for more details). It became

effective as a federal government standard on May 26, 2002 after

approval by the

Secretary of Commerce. AES is included in the ISO/IEC 18033-3

standard. AES is available in many different encryption packages, and is

the first publicly accessible and open

cipher

approved by the

National Security Agency (NSA) for

top secret information when used in an NSA approved cryptographic

module (see

Security of AES, below).

The name Rijndael (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈrɛindaːl])

is a play on the names of the two inventors. Strictly speaking, the AES

standard is a variant of Rijndael where the block size is restricted to

128 bits.

Description

of the cipher

AES is based on a design principle known as a

substitution-permutation network, and is fast in both software and

hardware.[6]

Unlike its predecessor DES, AES does not use a

Feistel network. AES is a variant of Rijndael which has a fixed

block size of 128

bits, and a

key

size of 128, 192, or 256 bits. By contrast, the Rijndael

specification per se is specified with block and key sizes that

may be any multiple of 32 bits, both with a minimum of 128 and a maximum

of 256 bits.

AES operates on a 4×4

column-major order matrix of bytes, termed the state,

although some versions of Rijndael have a larger block size and have

additional columns in the state. Most AES calculations are done in a

special

finite field.

The key size used for an AES cipher specifies the number of

repetitions of transformation rounds that convert the input, called the

plaintext, into the final output, called the ciphertext. The number of

cycles of repetition are as follows:

- 10 cycles of repetition for 128-bit keys.

- 12 cycles of repetition for 192-bit keys.

- 14 cycles of repetition for 256-bit keys.

Each round consists of several processing steps, including one that

depends on the encryption key itself. A set of reverse rounds are

applied to transform ciphertext back into the original plaintext using

the same encryption key.

High-level description of the algorithm

- KeyExpansion—round keys are derived from the cipher key using

Rijndael's key schedule

- Initial Round

- AddRoundKey—each byte of the state is combined with

the round key using bitwise xor

- Rounds

- SubBytes—a non-linear substitution step where each

byte is replaced with another according to a

lookup table.

- ShiftRows—a transposition step where each row of

the state is shifted cyclically a certain number of steps.

- MixColumns—a mixing operation which operates on the

columns of the state, combining the four bytes in each column.

- AddRoundKey

- Final Round (no MixColumns)

- SubBytes

- ShiftRows

- AddRoundKey

The SubBytes

step

In the

SubBytes step, each byte in the state is

replaced with its entry in a fixed 8-bit lookup table,

S;

bij =

S(aij).

In the SubBytes step, each byte in the state matrix

is replaced with a SubByte using an 8-bit

substitution box, the

Rijndael S-box. This operation provides the non-linearity in the

cipher.

The S-box used is derived from the

multiplicative inverse over

GF(28), known to have good non-linearity

properties. To avoid attacks based on simple algebraic properties, the

S-box is constructed by combining the inverse function with an

invertible

affine transformation. The S-box is also chosen to avoid any fixed

points (and so is a

derangement), and also any opposite fixed points.

The ShiftRows

step

In the

ShiftRows step, bytes in each row of the

state are shifted cyclically to the left. The number of

places each byte is shifted differs for each row.

The ShiftRows step operates on the rows of the state; it

cyclically shifts the bytes in each row by a certain

offset. For AES, the first row is left unchanged. Each byte of the

second row is shifted one to the left. Similarly, the third and fourth

rows are shifted by offsets of two and three respectively. For blocks of

sizes 128 bits and 192 bits, the shifting pattern is the same. Row n is

shifted left circular by n-1 bytes. In this way, each column of the

output state of the ShiftRows step is composed of bytes from

each column of the input state. (Rijndael variants with a larger block

size have slightly different offsets). For a 256-bit block, the first

row is unchanged and the shifting for the second, third and fourth row

is 1 byte, 3 bytes and 4 bytes respectively—this change only applies for

the Rijndael cipher when used with a 256-bit block, as AES does not use

256-bit blocks.

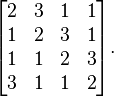

The

MixColumns step

In the

MixColumns step, each column of the state is

multiplied with a fixed polynomial

c(x).

In the MixColumns step, the four bytes of each column of the

state are combined using an invertible

linear transformation. The MixColumns function takes four

bytes as input and outputs four bytes, where each input byte affects all

four output bytes. Together with ShiftRows, MixColumns

provides

diffusion in the cipher.

During this operation, each column is multiplied by the known matrix

that for the 128-bit key is

-

-

The multiplication operation is defined as: multiplication by 1 means

no change, multiplication by 2 means shifting to the left, and

multiplication by 3 means shifting to the left and then performing

xor with the initial unshifted value. After shifting, a conditional

xor with 0x11B should be performed if the shifted value is larger

than 0xFF.

In more general sense, each column is treated as a polynomial over

GF(28) and is then multiplied modulo x4+1

with a fixed polynomial c(x) = 0x03 · x3 + x2 + x

+ 0x02. The coefficients are displayed in their

hexadecimal equivalent of the binary representation of bit

polynomials from GF(2)[x]. The MixColumns step can also

be viewed as a multiplication by a particular

MDS

matrix in a

finite field. This process is described further in the article

Rijndael mix columns.

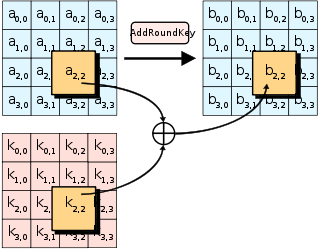

The

AddRoundKey step

In the

AddRoundKey step, each byte of the state is

combined with a byte of the round subkey using the

XOR operation (⊕).

In the AddRoundKey step, the subkey is combined with the

state. For each round, a subkey is derived from the main

key using

Rijndael's key schedule; each subkey is the same size as the state.

The subkey is added by combining each byte of the state with the

corresponding byte of the subkey using bitwise

XOR.

Optimization of the cipher

On systems with 32-bit or larger words, it is possible to speed up

execution of this cipher by combining the SubBytes and

ShiftRows steps with the MixColumns step by transforming

them into a sequence of table lookups. This requires four 256-entry

32-bit tables, and utilizes a total of four kilobytes (4096 bytes) of

memory — one kilobyte for each table. A round can then be done with 16

table lookups and 12 32-bit exclusive-or operations, followed by four

32-bit exclusive-or operations in the AddRoundKey step.[7]

If the resulting four kilobyte table size is too large for a given

target platform, the table lookup operation can be performed with a

single 256-entry 32-bit (i.e. 1 kilobyte) table by the use of circular

rotates.

Using a byte-oriented approach, it is possible to combine the

SubBytes, ShiftRows, and MixColumns steps into a

single round operation.[8]

Security

Until May 2009, the only successful published attacks against the

full AES were

side-channel attacks on some specific implementations. The

National Security Agency (NSA) reviewed all the AES finalists,

including Rijndael, and stated that all of them were secure enough for

U.S. Government non-classified data. In June 2003, the U.S. Government

announced that AES could be used to protect

classified information:

The design and strength of all key lengths of the AES algorithm

(i.e., 128, 192 and 256) are sufficient to protect classified

information up to the SECRET level. TOP SECRET information will

require use of either the 192 or 256 key lengths. The implementation

of AES in products intended to protect national security systems

and/or information must be reviewed and certified by NSA prior to

their acquisition and use."[9]

AES has 10 rounds for 128-bit keys, 12 rounds for 192-bit keys, and

14 rounds for 256-bit keys. By 2006, the best known attacks were on 7

rounds for 128-bit keys, 8 rounds for 192-bit keys, and 9 rounds for

256-bit keys.[10]

Known attacks

For cryptographers, a

cryptographic "break" is anything faster than a

brute force—performing one trial decryption for each key (see

Cryptanalysis). This includes results that are infeasible with

current technology. The largest successful publicly known

brute force attack against any block-cipher encryption was against a

64-bit RC5

key by

distributed.net in 2006.[11]

AES has a fairly simple algebraic description.[12]

In 2002, a theoretical attack, termed the "XSL

attack", was announced by

Nicolas Courtois and

Josef Pieprzyk, purporting to show a weakness in the AES algorithm

due to its simple description.[13]

Since then, other papers have shown that the attack as originally

presented is unworkable; see

XSL attack on block ciphers.

During the AES process, developers of competing algorithms wrote of

Rijndael, "...we are concerned about [its] use...in security-critical

applications."[14]

However, in October 2000 at the end of the AES selection process in,

Bruce Schneier, a developer of the competing algorithm

Twofish,

wrote that while he thought successful academic attacks on Rijndael

would be developed someday, "I do not believe that anyone will ever

discover an attack that will allow someone to read Rijndael traffic."[15]

On July 1, 2009, Bruce Schneier blogged[16]

about a

related-key attack on the 192-bit and 256-bit versions of AES,

discovered by

Alex Biryukov and Dmitry Khovratovich,[17]

which exploits AES's somewhat simple key schedule and has a complexity

of 2119. In December 2009 it was improved to 299.5.

This is a follow-up to an attack discovered earlier in 2009 by Alex

Biryukov, Dmitry Khovratovich, and Ivica Nikolić, with a complexity of 296

for one out of every 235 keys.[18]

Another attack was blogged by Bruce Schneier[19]

on July 30, 2009 and released as a preprint[20]

on August 3, 2009. This new attack, by Alex Biryukov, Orr Dunkelman,

Nathan Keller, Dmitry Khovratovich, and

Adi

Shamir, is against AES-256 that uses only two related keys and 239

time to recover the complete 256-bit key of a 9-round version, or 245

time for a 10-round version with a stronger type of related subkey

attack, or 270 time for an 11-round version. 256-bit AES uses

14 rounds, so these attacks aren't effective against full AES.

In November 2009, the first

known-key distinguishing attack against a reduced 8-round version of

AES-128 was released as a preprint.[21]

This known-key distinguishing attack is an improvement of the rebound or

the start-from-the-middle attacks for AES-like permutations, which view

two consecutive rounds of permutation as the application of a so-called

Super-Sbox. It works on the 8-round version of AES-128, with a time

complexity of 248, and a memory complexity of 232.

In July 2010 Vincent Rijmen published an ironic paper on

"chosen-key-relations-in-the-middle" attacks on AES-128.[22]

The first

key-recovery attacks on full AES were due to Andrey Bogdanov, Dmitry

Khovratovich, and Christian Rechberger, and were published in 2011.[23]

The attack is based on bicliques and is faster than brute force by a

factor of about four. It requires 2126.1 operations to

recover an AES-128 key. For AES-192 and AES-256, 2189.7 and 2254.4

operations are needed, respectively.

Side-channel

attacks

Side-channel attacks do not attack the underlying cipher and so have

nothing to do with its security as described here, but attack

implementations of the cipher on systems which inadvertently leak data.

There are several such known attacks on certain implementations of AES.

In April 2005,

D.J. Bernstein announced a cache-timing attack that he used to break

a custom server that used

OpenSSL's

AES encryption.[24]

The attack required over 200 million chosen plaintexts.[25]

The custom server was designed to give out as much timing information as

possible (the server reports back the number of machine cycles taken by

the encryption operation); however, as Bernstein pointed out, "reducing

the precision of the server's timestamps, or eliminating them from the

server's responses, does not stop the attack: the client simply uses

round-trip timings based on its local clock, and compensates for the

increased noise by averaging over a larger number of samples."

[24]

In October 2005, Dag Arne Osvik,

Adi

Shamir and Eran Tromer presented a paper demonstrating several

cache-timing attacks against AES.[26]

One attack was able to obtain an entire AES key after only 800

operations triggering encryptions, in a total of 65 milliseconds. This

attack requires the attacker to be able to run programs on the same

system or platform that is performing AES.

In December 2009 an attack on some hardware implementations was

published that used

differential fault analysis and allows recovery of a key with a

complexity of 232.[27]

In November 2010 Endre Bangerter, David Gullasch and Stephan Krenn

published a paper which described a practical approach to a "near real

time" recovery of secret keys from AES-128 without the need for either

cipher text or plaintext. The approach also works on AES-128

implementations that use compression tables, such as OpenSSL.[28]

Like some earlier attacks this one requires the ability to run

unprivileged code on the system performing the AES encryption, which may

be achieved by malware infection far more easily than commandeering the

root account.[29]

NIST/CSEC

validation

The

Cryptographic Module Validation Program (CMVP) is operated jointly

by the United States Government's

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Computer

Security Division and the

Communications Security Establishment (CSE) of the Government of

Canada. The use of cryptographic modules validated to NIST

FIPS 140-2 is required by the United States Government for

encryption of all data that has a classification of Sensitive but

Unclassified (SBU) or above. From NSTISSP #11, National Policy Governing

the Acquisition of Information Assurance: "Encryption products for

protecting classified information will be certified by NSA, and

encryption products intended for protecting sensitive information will

be certified in accordance with NIST FIPS 140-2."

[30]

The Government of Canada also recommends the use of

FIPS

140 validated cryptographic modules in unclassified applications of

its departments.

Although NIST publication 197 ("FIPS 197") is the unique document

that covers the AES algorithm, vendors typically approach the CMVP under

FIPS 140 and ask to have several algorithms (such as

Triple DES or

SHA1) validated at the same time. Therefore, it is rare to find

cryptographic modules that are uniquely FIPS 197 validated and NIST

itself does not generally take the time to list FIPS 197 validated

modules separately on its public web site. Instead, FIPS 197 validation

is typically just listed as an "FIPS approved: AES" notation (with a

specific FIPS 197 certificate number) in the current list of FIPS 140

validated cryptographic modules.

The Cryptographic Algorithm Validation Program (CAVP)[31]

allows for independent validation of the correct implementation of the

AES algorithm at a reasonable cost[citation

needed]. Successful validation results in being

listed on the NIST validations page. This testing is a pre-requisite for

the FIPS 140-2 module validation described below. However, successful

CAVP validation in no way implies that the cryptographic module

implementing the algorithm is secure. Lacking FIPS 140-2 validation or

specific approval by the NSA, a cryptographic module is not deemed

secure by the US Government and cannot be used to protect government

data.[30]

FIPS 140-2 validation is challenging to achieve both technically and

fiscally.[32]

There is a standardized battery of tests as well as an element of source

code review that must be passed over a period of a few weeks. The cost

to perform these tests through an approved laboratory can be significant

(e.g., well over $30,000 US)[32]

and does not include the time it takes to write, test, document and

prepare a module for validation. After validation, modules must be

re-submitted and re-evaluated if they are changed in any way. This can

vary from simple paperwork updates if the security functionality did not

change to a more substantial set of re-testing if the security

functionality was impacted by the change.

Test vectors

Test vectors are a set of known ciphers for a given input and key.

NIST distributes the reference of AES test vectors as

AES Known Answer Test (KAT) Vectors (in ZIP format).

Performance

High speed and low RAM requirements were criteria of the AES

selection process. Thus AES performs well on a wide variety of hardware,

from 8-bit

smart cards to high-performance computers.

On a

Pentium Pro, AES encryption requires 18 clock cycles / byte,[33]

equivalent to a throughput of about 11 MiB/s for a 200 MHz processor. On

a

Pentium M 1.7 GHz throughput is about 60 MiB/s.

On Intel i5/i7 CPUs supporting

AES-NI instruction set extensions throughput is about 400MiB/s per

thread.[citation

needed]